Coding mistakes in bioinformatics, their consequences for research, and how to correct them

Table of Contents

- The context: comparing gene annotation software

- The problem: inconsistencies between method and results

- The first bug: filtering hits with the wrong bit score threshold

- The second bug: string comparison of numerical bit score values

- The consequences: scientific conclusions might depend on incorrect annotations

- Conclusion

Modern biology research relies on countless computational tools and software created by hard-working people. The rapid progress of biological data expansion over the past two decades has forced many researchers into the position of ‘software developer’ to create the programs needed to analyze this vast data regardless of whether they’ve had training in development best practices, and the relentless pace of scientific research pushes everyone to quickly and efficiently publish, often leaving little time for fine-tuning analyses or validating results. In addition, typical academic budgets simply do not allow for large teams of professionals to support tool development, and development often stops (or at least substantially slows) once the tool’s associated paper is published. That’s just the reality of science in the computational era. We’re all just doing our best, you know?

Unfortunately, this punishing reality of rapidly releasing new bioinformatics tools to perform new analyses to publish new papers also means that the choices and mistakes we make in step 1 (tool development) can have far-reaching consequences for the biological conclusions we make based upon the output of those tools. Anyone who works with a computer for research these days (and that is a whole lot of us) grapples with this all the time – which program you use to do an analysis, and which parameters you choose while running the program, can greatly influence your final results.

And if your tool is available for other people to use, its sphere of influence is greatly expanded – the implementation choices you made are going to affect the conclusions of other scientists around the globe. Which is beautiful, and a really powerful mechanism of progress in science. But it also comes with a heavier responsibility, both on the part of the individuals developing tools and on the part of the individuals using them. If your code will be available and therefore potentially widely-used, it has to be correct. And if you are using someone else’s tool, you should probably understand what it is doing and be extra careful to validate the output.

Of course, that would happen in an ideal world, but we live in reality, which means that coding mistakes will sometimes be missed, and those mistakes will influence the downstream analyses and even results that end up getting published. If these issues come to light, it is usually difficult for everyone involved. Yet, because mistakes are inevitable, we as a community shouldn’t shy away from bringing them up and dealing with them together. After all, the most important thing is that even in our imperfect reality, a correction (of the bugs in the code and/or of any affected results and conclusions) is possible, and everyone’s science gets stronger afterwards.

The ability to correct the course of technical issues is one of the beauties and advantages of the open-source software movement, and is one reason why open science is so critical for research progress. If you don’t publish your programs and computational strategies openly, then the only likely person to find your mistakes is you, while others are limited to whatever insights they can draw from cross-checking the results (if they do that at all). But developing open-source tools spreads the risk and accountability, in a way. Other people can see and understand what is going on behind-the-scenes, and can propose changes to fix potential issues.

If you want an example of how this works, feel free to check out the anvi’o Issue page on Github, which features hundreds of bug reports in various stages of resolution (we appreciate everyone who takes the time to let us know about issues and do our best to keep up with fixing them 😅😭).

We’re telling you all this because it is, in fact, something that happened to us. And we wanted to share our experience, not only because those whose research results are impacted by it deserve to know, but also as a sort of reminder to everyone in the business of bioinformatics software development (ourselves included) that yes, development errors can happen, and yes, they can impact a lot of research, but they are fixable (especially with the help of open science) and everything will be okay.

The context: comparing gene annotation software

Here is the summary of what happened: we were looking into the gene annotation differences between two software, anvi’o and MicrobeAnnotator. We saw some really weird results, found a couple of bugs in the MicrobeAnnotator code, fixed those bugs, and everything made sense again. Boom! Open-source code to the rescue. But we couldn’t just move on with our lives without telling anyone about it, so here we are.

The full story starts like this. Kat was building an annotation pipeline and was looking for the best software to annotate KEGG Orthologs (KOs) from the KOfam database (Aramaki et al., 2020). She decided on trying MicrobeAnnotator (Ruiz-Perez et al., 2021). Christian (a student working alongside Kat), ran anvi’o (Eren et al., 2020) while waiting for development to complete. He noticed the sudden appearance of KOs that were missing in previous annotations using the pipeline! Perplexed, Kat compared anvi’o with MicrobeAnnotator, and figured out that they were yielding different annotations for the same input sequences. She reached out to Iva (the developer of the KO annotation program within anvi’o, which is anvi-run-kegg-kofams) and together, we started looking for the source of the inconsistent results.

For anyone who doesn’t know, both anvi’o and MicrobeAnnotator take an initially similar approach to annotating genes with KOs. Both of them download the publicly-available database of KOfam profiles (from here), which are Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) representing each family of proteins within the KEGG Ortholog database. They both run the HMMER software (hmmer.org) to query each input gene sequence against each HMM and obtain a similarity score (called a ‘bit score’) that measures how well the gene matches against the model. They also both initially filter out the strongest hits to each KOfam profile by using a bit score threshold, which is pre-defined for each HMM (as described in Aramaki et al., 2020) with the idea that bit scores above the threshold indicate the gene belongs to the protein family represented by the model, and bit scores below the threshold indicate that the gene belongs to a different protein family.

After that point, the two approaches diverge as they attempt to further curate the results. Since KOfam’s pre-defined bit score thresholds are occasionally too stringent for genes that slightly diverge from the reference sequences used to build a given HMM, which can lead to the disposal of otherwise strong matches, anvi-run-kegg-kofams includes an annotation heuristic to add back these annotations if they meet a set of (adjustable) criteria. You can learn more about it here. Meanwhile, MicrobeAnnotator’s next step is to further filter the KOfam hits so that it keeps only the best match to each gene (i.e., a single gene cannot have more than one KO annotation) by keeping only the hit with the highest bit score. It then goes on to iteratively check the yet-unannotated genes against a variety of other databases, including SwissProt, RefSeq, and trEMBL. For instance, if a gene doesn’t have an initial KO annotation from KOfam, the pipeline will attempt to annotate it with SwissProt, and if that still doesn’t yield a match, the pipeline will attempt to annotate it with RefSeq, and so on. At the very end, it aggregates all of those annotations into one big table. Due to the iterative nature of this algorithm, the annotations from the initial search against KOfam will always make it into the final annotation table (and will be the only annotation present for those genes, unless the pipeline is run with the --full flag, if we are reading the code right). These initial annotations were the most directly comparable to the ones yielded by anvi-run-kegg-kofams, so for the purposes of our satisfying our curiousity, we only focused on the output from their KOfam search.

In short, anvi’o tries to include more annotations, while MicrobeAnnotator tries to include fewer annotations, with one exception. In the case where a KOfam profile does not have an associated bit score threshold, the two tools do the opposite from what they normally do – anvi’o does not include hits to these KOs while MicrobeAnnotator does. The reason anvi’o doesn’t annotate threshold-less KOs is that without a threshold, we don’t have a strategy to distinguish between good and bad matches to the HMM (and we want to avoid introducing garbage annotations). Meanwhile, MicrobeAnnotator’s iterative annotation strategy adds alternative evidence that presumably helps people determine which hits are trustworthy.

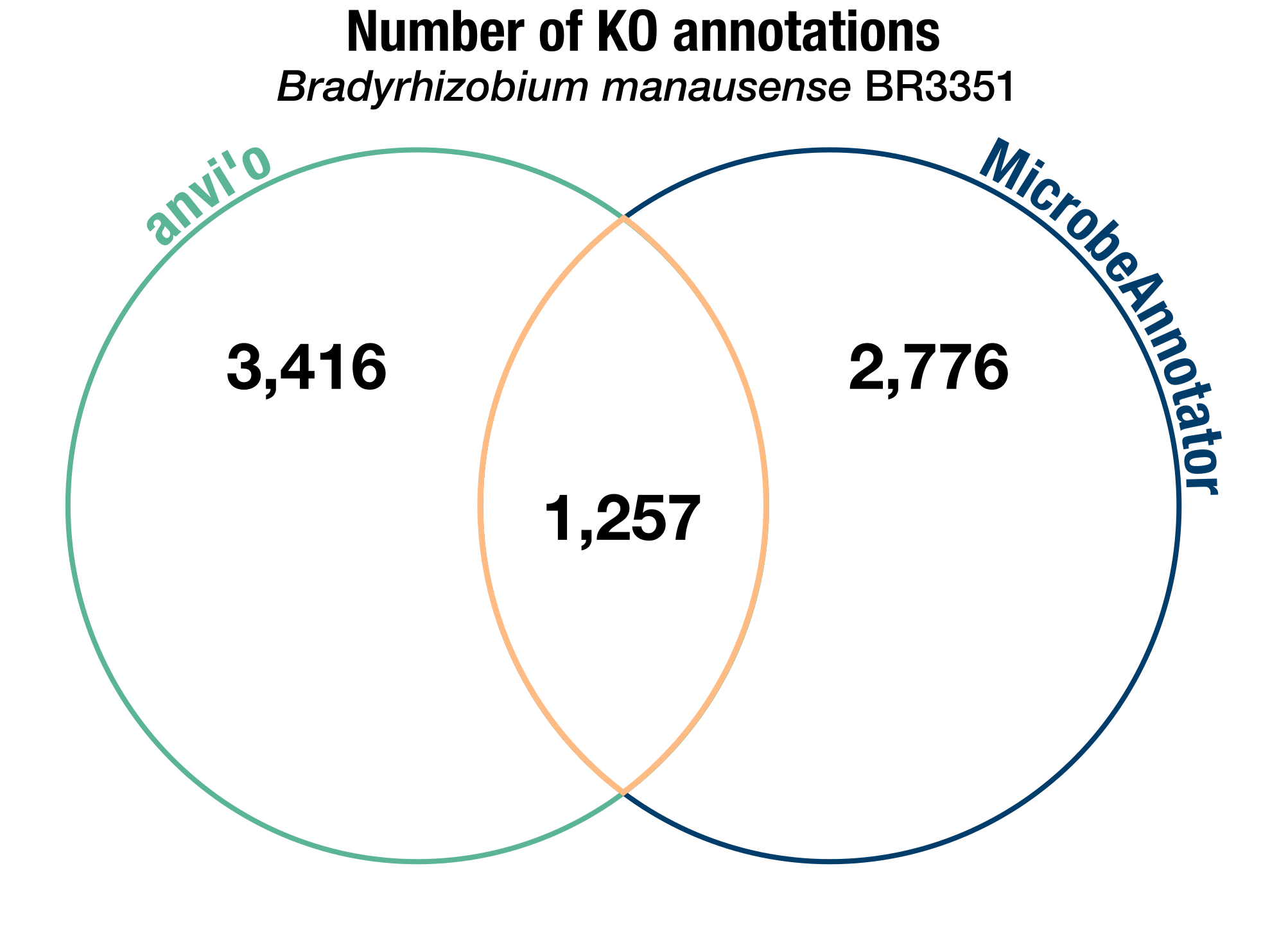

Given the same input gene sequences and using the same version of the KOfam database, these two programs should certainly yield some different annotations. And they did, but not in the way we expected them to. For instance, not counting the KOs without bit score thresholds (which anvi’o doesn’t try to annotate, as we mentioned), here is a comparison of the KO annotations resulting from each software on our test genome:

A Venn diagram of the number of KEGG Ortholog annotations identified by either anvi’o, MicrobeAnnotator, or both in the B. manausense BR3351 genome. Note that we don’t include the KOs without bit score thresholds in these counts.

The number of software-specific annotations was unusually high, considering the initial similarity in the annotation strategy of both tools. Knowing the methods, we expected to see a much higher number of ‘common’ annotations, some anvi’o-specific annotations (due to our heuristic for adding back hits below the bit score threshold), and little-to-no MicrobeAnnotator-specific annotations.

Some methodological details about our investigations

In the following sections, we’ll show some data from our investigations into the MicrobeAnnotator results. We ran our tests on several genomes, but for brevity’s sake we will only include the results from one genome in this post. Specifically, we used the reference genome for Bradyrhizobium manausense BR3351, which is publicly available on NCBI under the RefSeq accession number GCF_001440035.1 and BioProject PRJNA295814.

We ran both MicrobeAnnotator and the anvi’o program anvi-run-kegg-kofams on our test genomes. To keep the KOfam database version consistent between the two software, we downloaded this database using the respective programs microbeannotator_db_builder and anvi-setup-kegg-data on the same day: December 15th, 2023. We verified that the two databases contained the same profiles and profile information by checking that they included an identical ko_list file, which stores all profiles and their bit score thresholds.

Here are the loops to annotate each genome, first with anvi’o and second with MicrobeAnnotator, so that you can see which parameters we used for each:

# run anvi'o on each db

conda activate anvio-8 # this loads the latest stable release of anvi'o, v8

for db in dbs_and_fastas/*.db; do \

name=$(basename $db .db); \

anvi-run-kegg-kofams -c $db --kegg-data-dir KEGG_12_15_2023 -T 5 --just-do-it; \

anvi-export-functions -c $db --annotation-sources KOfam -o anvio_output/${name}_KOfam.txt; \

# get protein sequences into a FASTA file for MicrobeAnnotator input

anvi-get-sequences-for-gene-calls -c $db --get-aa-sequences -o dbs_and_fastas/${name}_proteins.fasta;

done

# run microbeannotator on each genome

conda deactivate

conda activate microbeannotator

for db in dbs_and_fastas/*.db; do \

name=$(basename $db .db); \

microbeannotator -i dbs_and_fastas/${name}_proteins.fasta -o microbeannotator_output/${name} -m diamond --light -d MicrobeAnnotator_DB -t 5; \

done

Note that we first converted each genome’s FASTA file into an anvi’o contigs database using the program anvi-gen-contigs-database. This included a step to run Prodigal (Hyatt et al. 2010) for gene-calling. To ensure we used the same gene sequences as input for MicrobeAnnotator, we exported these genes from the database using anvi-get-sequences-for-gene-calls (the command for this is also shown in the code block above).

To compare the two sets of KOfam annotations, we looked at the output file from anvi-export-functions generated within the anvi’o loop above (i.e., anvio_output/Bradyrhizobium_manausense_BR3351_KOfam.txt), and the MicrobeAnnotator output generated within the kofam_results folder of its output directory. The latter includes two files, one ending in *.kofam that should contain all hits that passed the bit score threshold (i.e., Bradyrhizobium_manausense_BR3351_proteins.fasta.kofam), and one ending in *.filt that should contain the final, filtered set of best matches to a given gene (i.e., Bradyrhizobium_manausense_BR3351_proteins.fasta.kofam.filt).

The problem: inconsistencies between method and results

We ran some tests, and our investigation of the differentially-present annotations showed that the final results from MicrobeAnnotator’s KOfam annotation step included some hits with a bit score below the threshold for the relevant KOfam profile. That was a bit strange, considering that their approach should exclude weak hits like this.

For example, the KOfam profile for K00119 has a full bit score threshold of 510.70, according to the ko_list file that was downloaded alongside the profiles. However, when we looked at the final, filtered output from MicrobeAnnotator (files ending in *.filt), we saw two hits for K00119 that had full bit scores of 80.6 and 98.3, respectively. Here is the beginning of the *.filt output file from MicrobeAnnotator when run on Bradyrhizobium manausense BR3351:

$ head microbeannotator_output/Bradyrhizobium_manausense_BR3351/kofam_results/Bradyrhizobium_manausense_BR3351_proteins.fasta.kofam.filt

# ---- full_sequence ---- ---- best_1_domain ---- --- --- --- domain number estimation --- --- description_of_target

# query_name accession target_name accession score_type E-value score bias E-value score bias exp reg clu ov env dom rep inc description_of_target

# ----------- --------- ---------- --------- ---------- ------- ----- ---- ------- ----- ---- --- --- --- -- --- --- --- --- ---------------------

6333 - K00003 - domain 1.4e-152 509.1 17.8 1.5e-152 508.9 17.8 1.0 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 homoserine dehydrogenase [EC:1.1.1.3]

1672 - K00119 - full 5.2e-23 80.6 8.9 4.2e-21 74.4 8.9 2.5 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 alcohol dehydrogenase (nicotinoprotein) [EC:1.1.99.36]

4973 - K00119 - full 2.3e-28 98.3 6.4 8.9e-28 96.3 6.4 1.8 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 alcohol dehydrogenase (nicotinoprotein) [EC:1.1.99.36]

8268 - K20590 - - 8.5e-19 66.5 5.1 9.5e-19 66.4 5.1 1.1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 gentamicin A2 dehydrogenase [EC:1.1.1.-]

1898 - K00012 - full 7.2e-139 463.2 0.1 7.9e-139 463.1 0.1 1.0 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 UDPglucose 6-dehydrogenase [EC:1.1.1.22]

4022 - K00012 - full 7.2e-139 463.2 0.1 7.9e-139 463.1 0.1 1.0 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 UDPglucose 6-dehydrogenase [EC:1.1.1.22]

537 - K00012 - full 7.2e-139 463.2 0.1 7.9e-139 463.1 0.1 1.0 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 UDPglucose 6-dehydrogenase [EC:1.1.1.22]

We convert the first 7 columns to table form below and put the relevant data in bold so you can see a bit better:

| query_name | accession | target_name | accession | score_type | (full_sequence) E-value | (full_sequence) score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6333 | - | K00003 | - | domain | 1.4e-152 | 509.1 |

| 1672 | - | K00119 | - | full | 5.2e-23 | 80.6 |

| 4973 | - | K00119 | - | full | 2.3e-28 | 98.3 |

| 8268 | - | K20590 | - | - | 8.5e-19 | 66.5 |

| 1898 | - | K00012 | - | full | 7.2e-139 | 463.2 |

| 4022 | - | K00012 | - | full | 7.2e-139 | 463.2 |

| 537 | - | K00012 | - | full | 7.2e-139 | 463.2 |

Those two hits to K00119 should not have made it past the first filtering step, since both 80.6 and 98.3 are less than the threshold of 510.70.

You might notice in this output table that K20590 has no score type. That is because it doesn’t have an associated bit score threshold. MicrobeAnnotator keeps all hits to KO profiles like this one, so it is normal to see it here.

Things got even weirder when we dug deeper. We looked at the intermediate output files (ending in *.kofam) to see the hits that didn’t pass the second filter for the ‘best match’ to a given gene, and saw that in some cases, the best match was not actually the match with the highest bit score.

Here again, the K00119 hits provide a good example. In the table above, gene 1672 has a hit to K00119 with a bit score of 80.6. That score is not very high, so why was it chosen as the ‘best match’ to this gene? We can take one step back and look at the *.kofam output file, which will list all of the hits to this gene before the filter for ‘best match’ was applied:

$ grep 1672 microbeannotator_output/Bradyrhizobium_manausense_BR3351/kofam_results/Bradyrhizobium_manausense_BR3351_proteins.fasta.kofam

1672 - K00004 - domain 1.7e-122 407.9 0.3 1.9e-122 407.8 0.3 1.0 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 (R,R)-butanediol dehydrogenase / meso-butanediol dehydrogenase / diacetyl reductase [EC:1.1.1.4 1.1.1.- 1.1.1.303]

1672 - K05351 - domain 2.2e-77 259.6 0.1 3.4e-77 259.0 0.1 1.2 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 D-xylulose reductase [EC:1.1.1.9]

1672 - K23493 - - 2.5e-08 32.2 1.0 7.8e-08 30.6 1.0 1.7 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 geissoschizine synthase [EC:1.3.1.36]

1672 - K14577 - - 1.3e-09 36.0 1.0 0.00038 18.1 0.1 2.1 2 0 0 2 2 2 2 aliphatic (R)-hydroxynitrile lyase [EC:4.1.2.46]

1672 - K08322 - domain 1.2e-85 286.5 0.7 1.4e-85 286.3 0.7 1.0 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 L-gulonate 5-dehydrogenase [EC:1.1.1.380]

1672 - K20434 - full 6.4e-15 53.7 5.4 1.6e-14 52.4 4.3 2.0 2 1 0 2 2 2 1 cyclitol reductase

1672 - K00119 - full 5.2e-23 80.6 8.9 4.2e-21 74.4 8.9 2.5 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 alcohol dehydrogenase (nicotinoprotein) [EC:1.1.99.36]

1672 - K19961 - full 6.8e-42 142.7 0.3 7.9e-42 142.5 0.3 1.0 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 6-hydroxyhexanoate dehydrogenase [EC:1.1.1.258]

1672 - K05352 - full 2.6e-16 58.3 0.0 3.4e-16 57.9 0.0 1.0 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 ribitol-5-phosphate 2-dehydrogenase (NADP+) [EC:1.1.1.405]

1672 - K21190 - full 2.1e-30 104.9 3.5 2.8e-30 104.5 3.5 1.1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 dehydrogenase

1672 - K18125 - full 1.7e-21 75.7 0.7 8.7e-20 70.0 0.7 2.0 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 aldose 1-dehydrogenase [NAD(P)+] [EC:1.1.1.359]

1672 - K13548 - domain 9.5e-56 188.1 5.8 1.4e-55 187.5 5.8 1.2 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 2-deoxy-scyllo-inosamine dehydrogenase [EC:1.1.1.329]

1672 - K14465 - domain 3.6e-59 199.2 8.5 2.4e-39 134.0 1.4 2.2 1 1 1 2 2 2 2 succinate semialdehyde reductase (NADPH) [EC:1.1.1.-]

There are a lot of hits, so here again we convert the first 7 columns to a table form, and put the hit to K00119 in bold:

| query_name | accession | target_name | accession | score_type | (full_sequence) E-value | (full_sequence) score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1672 | - | K00004 | - | domain | 1.7e-122 | 407.9 |

| 1672 | - | K05351 | - | domain | 2.2e-77 | 259.6 |

| 1672 | - | K23493 | - | - | 2.5e-08 | 32.2 |

| 1672 | - | K14577 | - | - | 1.3e-09 | 36.0 |

| 1672 | - | K08322 | - | domain | 1.2e-85 | 286.5 |

| 1672 | - | K20434 | - | full | 6.4e-15 | 53.7 |

| 1672 | - | K00119 | - | full | 5.2e-23 | 80.6 |

| 1672 | - | K19961 | - | full | 6.8e-42 | 142.7 |

| 1672 | - | K05352 | - | full | 2.6e-16 | 58.3 |

| 1672 | - | K21190 | - | full | 2.1e-30 | 104.9 |

| 1672 | - | K18125 | - | full | 1.7e-21 | 75.7 |

| 1672 | - | K13548 | - | domain | 9.5e-56 | 188.1 |

| 1672 | - | K14465 | - | domain | 3.6e-59 | 199.2 |

If our instincts were correct, then the hit with the highest bit score – the one in the first row, the hit to K00004 with a bit score of 407.9 – should have been selected as the ‘best match’ for gene 1672, since 407.9 > 80.6. Yet, the hit to K00119 made it into the final *.filt output file instead.

Both of these observations were inconsistent with what we knew of the methodology of MicrobeAnnotator. So, to get some answers, we had to dig into the code. Luckily, we could do that, because the MicrobeAnnotator code is open-source on Github.

The first bug: filtering hits with the wrong bit score threshold

First, a brief overview of the structure of MicrobeAnnotator. To avoid copy-pasting all the code here, we’ll simply link to the relevant locations in its Github repository:

- the main program is encoded in the binary file

microbeannotator. This is what you call from the command-line to run the pipeline. - the behind-the-scenes magic happens in this folder containing Python classes for each part of the pipeline.

- specifically, the code to handle most of the KOfam annotation decisions is within the module

hmmsearch.py, which has functions to run HMMER, parse the results, select the best match per gene, etc.

Our first task was to figure out what was happening to allow HMM hits with scores below the bit score threshold to pass through the first filter. That filter happens in hmmsearch.py, in the aptly-named hmmer_filter() function (which is here in the codebase).

We added some print statements to see what was going on when this function was executed (very old-school, we know). Our modifications (marked with ## ADDED) made the function look like this:

def hmmer_filter(

hmmsearch_result: List[hmmer.tbl.TBLRow]) -> List[hmmer.tbl.TBLRow]:

# Initialize list with filtered results

hmmsearch_result_filt = []

# Get model name, threshold and score_type

model_name = hmmsearch_result[0].query.name

threshold = hmm_model_info[model_name].threshold

score_type = hmm_model_info[model_name].score_type

print(f"Filtering hits for model {model_name} with {score_type} threshold {threshold}") ## ADDED

if score_type == 'full':

for result in hmmsearch_result:

if float(result.full_sequence.score) >= threshold:

hmmsearch_result_filt.append(result)

print(f"Hit with score {float(result.full_sequence.score)} passed filter") ## ADDED

elif score_type == 'domain':

for result in hmmsearch_result:

if float(result.best_1_domain.score) >= threshold:

hmmsearch_result_filt.append(result)

print(f"Hit with domain score {float(result.best_1_domain.score)} passed filter") ## ADDED

else:

for result in hmmsearch_result:

hmmsearch_result_filt.append(result)

print("Hit with no threshold passed filter") ## ADDED

return hmmsearch_result_filt

As you can see, we print the KOfam model information each time a model is loaded from the global hmm_model_info data structure, and then we print each time a hit passes the filter. We ran the modified code on one test genome, and stored the log output in a file called microbeannotator.log.

When we checked the log file, we noticed that model information is only being loaded 27 times, despite the fact that over 26,000 KO profiles exist in the KOfam database:

$ grep "Filtering hits for model" microbeannotator.log

Filtering hits for model K03088 with domain threshold 97.23

Filtering hits for model K17081 with full threshold 414.0

Filtering hits for model K16413 with - threshold -

Filtering hits for model K00001 with domain threshold 379.83

Filtering hits for model K01363 with domain threshold 228.63

Filtering hits for model K21811 with full threshold 449.23

Filtering hits for model K21536 with full threshold 148.83

Filtering hits for model K25071 with full threshold 765.63

Filtering hits for model K00790 with domain threshold 172.07

Filtering hits for model K07037 with full threshold 218.93

Filtering hits for model K08071 with full threshold 378.6

Filtering hits for model K03446 with domain threshold 350.63

Filtering hits for model K09726 with full threshold 179.77

Filtering hits for model K24847 with full threshold 674.23

Filtering hits for model K05540 with full threshold 282.07

Filtering hits for model K17241 with full threshold 288.03

Filtering hits for model K19168 with domain threshold 24.5

Filtering hits for model K11354 with full threshold 460.53

Filtering hits for model K18130 with full threshold 215.6

Filtering hits for model K10022 with domain threshold 343.67

Filtering hits for model K16649 with full threshold 152.1

Filtering hits for model K08979 with full threshold 166.07

Filtering hits for model K18304 with full threshold 218.1

Filtering hits for model K19429 with full threshold 223.6

Filtering hits for model K23661 with full threshold 205.5

Filtering hits for model K15950 with full threshold 1043.53

Filtering hits for model K11061 with domain threshold 563.5

$ grep -c "Filtering hits for model" microbeannotator.log

27

Looking back at the hmmer_filter() function, it becomes clear that this line is the culpit:

model_name = hmmsearch_result[0].query.name

Only the very first KOfam (the one at index 0) in the set of hmmsearch results being passed to this function is used to extract the bit score type and threshold from hmm_model_info. This is not necessarily a bad thing by itself, but it requires the assumption that the hmmsearch_result variable contains hits to only a single KO.

Unfortunately, that assumption is incorrect. In order to more efficiently run the HMM search, MicrobeAnnotator splits up the thousands of KOfam models into 53 sets of about 500 profiles each. There are 18 sets specific to prokaryotic protein families, 26 sets specific to eukaryotic proteins, 5 common sets and 4 ‘independent’ sets. These are all stored in the MicrobeAnnotator database at the path MicrobeAnnotator_DB/kofam_data/profiles/:

$ ls MicrobeAnnotator_DB/kofam_data/profiles/*.model

MicrobeAnnotator_DB/kofam_data/profiles/common_1.model

MicrobeAnnotator_DB/kofam_data/profiles/common_2.model

MicrobeAnnotator_DB/kofam_data/profiles/common_3.model

MicrobeAnnotator_DB/kofam_data/profiles/common_4.model

MicrobeAnnotator_DB/kofam_data/profiles/common_5.model

MicrobeAnnotator_DB/kofam_data/profiles/eukaryote_1.model

(.....)

MicrobeAnnotator_DB/kofam_data/profiles/prokaryote_8.model

MicrobeAnnotator_DB/kofam_data/profiles/prokaryote_9.model

This enables multi-threading of the HMM search. The software determines each possible pair of input protein FASTA files and model sets (here), and then calls the search function hmmer_search() independently on each pair so that they can be concurrently processed if more than one thread is available (here). But even if only one thread is used for the annotation, the search is still run independently on each set of KOfam profiles, meaning that the hmmsearch_result variable passed to the hmmer_filter() function will contain the hits from all models in a given set.

This means that the filtering function only uses the bit score threshold from the first KO in each set to remove weak hits from all the profiles in the set.

If there are 53 sets of KOfam profiles, why did we see only 27 models being loaded in the log? By default, MicrobeAnnotator assumes that you are working with prokaryotic genomes and will only run the non-eukaryotic models against the input proteins (if you pass the --eukaryote flag, it will instead use the eukaryotic models). The 18 prokaryotic sets plus the 5 common sets and 4 ‘independent’ sets add up to 27 total. And indeed, when we searched for the initial KOfam in each of these sets, the model names matched up exactly to the ones in the microbeannotator.log output that were used for filtering the hits (albeit out of order):

$ for f in MicrobeAnnotator_DB/kofam_data/profiles/common*.model \

MicrobeAnnotator_DB/kofam_data/profiles/prokaryote*.model \

MicrobeAnnotator_DB/kofam_data/profiles/independent*.model; do \

head $f | grep NAME; \

done

NAME K00001

NAME K01363

NAME K03088

NAME K07994

NAME K17081

NAME K00790

NAME K18130

NAME K18304

NAME K09725

NAME K08979

NAME K15950

NAME K11061

NAME K16649

NAME K19429

NAME K23661

NAME K02595

NAME K11354

NAME K24847

NAME K05540

NAME K03446

NAME K17241

NAME K09726

NAME K11008

NAME K13477

NAME K25279

NAME K15947

NAME K15995

Furthermore, when we looked for K00119 in the model sets, we saw that it belongs to the set called prokaryote_2.model. The first KO in that set is K02595, which has a bit score threshold of 50.27 – and that is why the weak hits to K00119 (with scores of 80.6 and 98.3) passed this filter:

$ grep K00119 MicrobeAnnotator_DB/kofam_data/profiles/*.model

MicrobeAnnotator_DB/kofam_data/profiles/prokaryote_2.model:NAME K00119

$ head MicrobeAnnotator_DB/kofam_data/profiles/prokaryote_2.model | grep NAME

NAME K02595

$ grep K02595 MicrobeAnnotator_DB/kofam_data/ko_list

K02595 50.27 full all 1.000000 424 370 296 128 3.81 0.590 nitrogenase-stabilizing/protective protein

It seems likely that the developers initially designed the hmmer_filter() function to run on hits from one KOfam profile at a time, but when improving the pipeline’s performance with multi-threading across model sets, they did not amend this function so that it would assume the input contains more than one KO and read the correct bit score threshold for each. An understandable oversight to be sure, especially considering that the pipeline runs without any errors to indicate that something is wrong.

What are the consequences of this bug? Well, the first problem is that when the initial KO has a bit score below the true bit score for a given profile (or no bit score at all), the hmmer_filter() function will erroneously keep weak hits to that profile; i.e., introducing false positives into the final annotation results. The second problem is that when the initial KO has a bit score above the true bit score for a given profile, the hmmer_filter() function will erroneously remove strong hits to that profile; i.e., leading to false negatives in the final results.

We wrote a little Python script to quantify the number of false positives in the annotations for our test genomes. If you want to see the script, it is in the show/hide box below. For the Bradyrhizobium manausense BR3351 genome, there were 2,852 annotations with bit scores lower than the original threshold for the KO in question. With a total of 4,366 annotations in the results from MicrobeAnnotator, that means false positives make up ~65% of the annotations for this particular genome. For our other test genomes, the percentage of false positives ranged from 47% to 62%. There seemed to be a positive correlation between genome size (as measured by total number of genes) and the percentage of false positives, which makes logical sense, since having more genes leads to more weak hits that can accidentally be included in the final results.

Show/Hide A script to quantify false positives

#!/usr/bin/env python

# A script to count the number of false positive annotations from MicrobeAnnotator output

# Usage: python count_false_positives.py PATH_TO_ANNOTATION_OUTPUT_DIRECTORY

# see below for expected directory structure of PATH_TO_ANNOTATION_OUTPUT_DIRECTORY

import os

import sys

# command-line argument

PATH_TO_ANNOTATION_OUTPUT=sys.argv[1] # path to the microbeannotator output files (each test genome has its own directory inside this one)

## CHANGE THESE INPUTS FOR ALTERNATIVE DIRECTORY SETUPS

PATH_TO_MICROBEANNOTATOR_DB="../../MicrobeAnnotator_DB/" # path to the database set up by microbeannotator_db_builder

# this list holds the name of each genome annotated by microbeannotator, to be used in building the file names later

# as in "Bradyrhizobium_manausense_BR3351/kofam_results/Bradyrhizobium_manausense_BR3351_proteins.fasta.kofam.filt"

genomes_to_process = ["Bradyrhizobium_manausense_BR3351",]

ko_list = os.path.join(PATH_TO_MICROBEANNOTATOR_DB, "kofam_data/ko_list")

ko_dict = {}

ko_file = open(ko_list, 'r')

for line in ko_file.readlines():

line = line.strip()

entries = line.split()

if entries[0] == 'knum':

continue

else:

if entries[1] == '-':

ko_dict[entries[0]] = {'threshold': None, 'score_type': entries[2]}

else:

ko_dict[entries[0]] = {'threshold': float(entries[1]), 'score_type': entries[2]}

for g in genomes_to_process:

filt_output_file = os.path.join(PATH_TO_ANNOTATION_OUTPUT, f"{g}/kofam_results/{g}_proteins.fasta.kofam.filt")

incorrect_annotations = []

with open(filt_output_file, 'r') as filt:

for line in filt.readlines():

if line.startswith("#"):

continue;

else:

hit_data = line.strip().split()

ko = hit_data[2]

full_bitscore = float(hit_data[6])

domain_bitscore = float(hit_data[9])

if ko_dict[ko]['threshold'] is None:

continue;

if ko_dict[ko]['score_type'] == 'full' and full_bitscore < ko_dict[ko]['threshold']:

incorrect_annotations.append((ko, full_bitscore, ko_dict[ko]['threshold']))

elif ko_dict[ko]['score_type'] == 'domain' and domain_bitscore < ko_dict[ko]['threshold']:

incorrect_annotations.append((ko, domain_bitscore, ko_dict[ko]['threshold']))

print(f"for {g}, the number of filtered annotations with bitscore less than the threshold is {len(incorrect_annotations)}")

We didn’t quantify the number of false negatives. Doing that would require us to modify the MicrobeAnnotator code so that it permanently stores the initial (pre-filter) HMMER search results, which is currently put into a temporary file that is automatically deleted post-execution (see the relevant code here).

The second bug: string comparison of numerical bit score values

Next, we investigated why the hit with the highest bit score for a given gene was not always selected as the ‘best match’ for the gene. The function to determine the best match is best_match_selector(), which is also part of the hmmsearch.py model (here).

To summarize, best_match_selector() reads the *.kofam output file containing all hits that passed the initial bit score-based filter. Each time it finds a new gene, it saves the first hit for that gene to a dictionary of ‘best matches’. Every time it finds another hit for that gene, it checks to see which hit has the higher bit score – if the original hit does, the entry for that gene in the best match dictionary stays the same, and if not, that entry gets replaced with the new hit. After processing all hits, the best matches in the dictionary get stored to the *.filt output file.

The logic in the code is exactly this, so it was difficult to see where the problem was coming from. However, we had a suspicion that it had something to do with reading the results from a text file. So we opened up the Python interpreter on the command line and ran the bit score comparison code from the best_match_selector() function, using one of the *.kofam output files from our test genomes as input. We added some print statements again, and ultimately the code we ran looked like this (once again, our additions are marked with ## ADDED):

# note that we set raw_results to be equal to a *.kofam output file first

with open(raw_results, 'r') as infile:

best_matches = {};

for line in infile:

record = line.strip().split('\t');

if record[0] not in best_matches:

best_matches[record[0]] = [record[6], line];

else:

if record[6] > best_matches[record[0]][0]:

print(f"old record has {best_matches[record[0]][0]}, new has {record[6]}") ## ADDED

print(f"type of old record: {type(best_matches[record[0]][0])}, type of new: {type(record[6])}") ## ADDED

best_matches[record[0]] = [record[6], line];

Basically, we run the same comparison logic as the original best_match_selector() function, but whenever we find a new hit that has a higher bit score than the one in the dictionary, we print out both the bit score values and the type of those values). Then, we looked through the output to see where the comparisons were going wrong.

Here is one example of what we saw:

old record has 117.8, new has 23.8

type of old record: <class 'str'>, type of new: <class 'str'>

This gave us the answer to the mystery: the code was indeed comparing bit scores, but the bit scores were loaded from the input file as strings, not as floating-point numbers. In Python, string comparison and numeric comparison are done in exactly the same way (with operators like < and >), and as long as the types of the variables on either side of the operator are the same, Python will not complain. When those variables are both numbers, the comparison is numeric, but when those variables are strings, the comparison is alphabetical. From an alphabetical perspective, the string "117.8" comes before the string "23.8". You can check this yourself in the Python interpreter, if you’d like:

>>> '117.8' < '23.8'

True

>>> '89' > '203'

True

>>> '914' < '10'

False

So, the reason that K00119 ended up as the ‘best match’ for gene 1672 is because the bitscore comparison between that hit and the one for K00004 (the actual best match) looked like this:

>>> '80.6' > '407.9'

True

Whoops. We love Python, but clearly its lack of (required) explicit typing can cause problems.

We say ‘required’ there because you can actually make Python variables explicitly typed since Python 3.6. It’s just not required, and since it’s convenient and faster not to do it, a lot of people (including most of the current anvi’o developers 😅) don’t.

The consequences? A lot of the hits in the *.filt output file are not actually the best match for the given gene. Plus, this issue compounds the previous bug – first, a lot of weak hits make it through the bit score filter, and then the string comparison makes it more likely for weak hits to end up in the final annotation output.

We quantified the number of hits that weren’t actually the ‘best match’ by comparing the *.kofam output with the *.filt output, using another Python script (see it in the Show/Hide box below). For our favorite test genome B. manausense BR3351, we found 1,692 incorrect best matches out of 4,366 genes, for a percentage of ~39%. For the other test genomes, this percentage ranged from 21% to 35%.

Show/Hide A script to quantify false best matches

#!/usr/bin/env python

# A script to count the number of false positive annotations from MicrobeAnnotator output

# Usage: python count_false_best_matches.py PATH_TO_ANNOTATION_OUTPUT_DIRECTORY

# see below for expected directory structure of PATH_TO_ANNOTATION_OUTPUT_DIRECTORY

import os

import sys

# command-line argument

PATH_TO_ANNOTATION_OUTPUT=sys.argv[1] # path to the microbeannotator output files (each test genome has its own directory inside this one)

## CHANGE THESE INPUTS FOR ALTERNATIVE DIRECTORY SETUPS

PATH_TO_MICROBEANNOTATOR_DB="../../MicrobeAnnotator_DB/" # path to the database set up by microbeannotator_db_builder

# this list holds the name of each genome annotated by microbeannotator, to be used in building the file names later

# as in "Bradyrhizobium_manausense_BR3351/kofam_results/Bradyrhizobium_manausense_BR3351_proteins.fasta.kofam.filt"

genomes_to_process = ["Bradyrhizobium_manausense_BR3351",]

for g in genomes_to_process:

kofam_output_file = os.path.join(PATH_TO_ANNOTATION_OUTPUT, f"{g}/kofam_results/{g}_proteins.fasta.kofam")

filt_output_file = os.path.join(PATH_TO_ANNOTATION_OUTPUT, f"{g}/kofam_results/{g}_proteins.fasta.kofam.filt")

# get the reported best matches

filt_annotations = {}

with open(filt_output_file, 'r') as filt:

for line in filt.readlines():

if line.startswith("#"):

continue

else:

hit_data = line.strip().split()

gene = hit_data[0]

ko = hit_data[2]

filt_annotations[gene] = ko

# get the true best matches

best_matches = {}

with open(kofam_output_file, 'r') as kof:

for line in kof.readlines():

if line.startswith("#"):

continue

else:

hit_data = line.strip().split()

gene = hit_data[0]

ko = hit_data[2]

full_bitscore = float(hit_data[6])

if gene not in best_matches:

best_matches[gene] = (ko, full_bitscore)

else:

prev_bitscore = best_matches[gene][1]

if full_bitscore > prev_bitscore:

best_matches[gene] = (ko, full_bitscore)

# compare true to reported

genes_with_wrong_best_match = []

for gene, best_match_tuple in best_matches.items():

best_ko = best_match_tuple[0]

if filt_annotations[gene] != best_ko:

genes_with_wrong_best_match.append(gene)

print(f"for {g}, the number of genes with the wrong best match annotation is {len(genes_with_wrong_best_match)}")

Soon after we submitted the pull-request and an issue for the developers of MicrobeAnnotator to consider these solutions, we were positively surprised to see a message by Brendan Daisley, who is currently a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Guelph studying microbial diversity and host-microbe interations.

Brendan had observed similar irregularities and had also been digging into the code to find their origins. Seeing these fixes, Brendan in fact took the time to perform independent tests using a Parvimonas micra strain, and confirm that the fixes seem to address the problem with following tables for Bug 1:

| False positive annotations | Total annotations | % false positives | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before fix | 318 | 707 | 44.9% |

| After fix | 0 | 943 | 0.0 % |

and for Bug 2:

| Incorrect best matches | Total annotations | % incorrect best matches | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before fix | 159 | 707 | 22.5% |

| After fix | 0 | 943 | 0.0 % |

We thank Brendan for demonstrating the best of open source and open science communities.

The consequences: scientific conclusions might depend on incorrect annotations

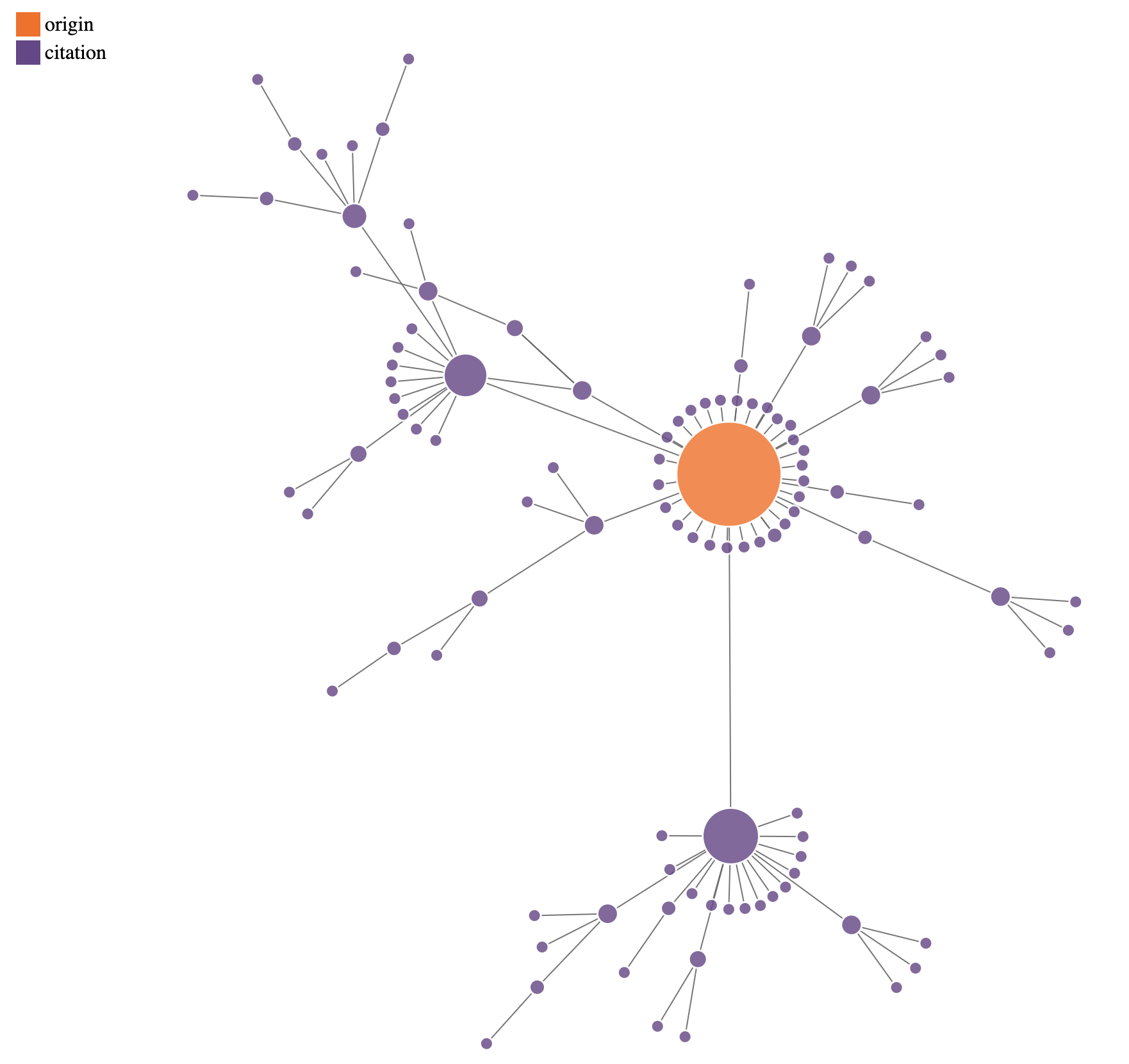

Obviously, a program that regularly yields over 50% poor annotations is a bit scary when you think about the downstream effects. People use this tool for their science, and that means they could be making conclusions based upon incorrect or missing annotations. We didn’t have the throughput to check the publications utilizing MicrobeAnnotator, but here is a network showing all of the content on Google Scholar that is linked to the MicrobeAnnotator publication via citations:

A citation tree originating from the MicrobeAnnotator paper (orange node) to other publications on Google Scholar (purple nodes), as of January 2024. Edges represent citations, and node size scales proportionally to the number of outgoing edges.

Bugs like this have potentially far-reaching effects on biological research. However, it is important to realize that things likely aren’t as bad as this network suggests. In this particular case, the MicrobeAnnotator pipeline reports metadata like e-values alongside each annotation, which means researchers don’t have to take the annotation results at face value (more on this below). Some of the erroneous annotations could also still be in the correct general “ballpark” of predicted function, as the misannotated genes would still typically have some degree of actual homology to their assigned KOfams (for example, a shared fold or domain). Additionally, just because a software is cited does not imply its results were used as the basis of a scientific conclusion.

One caveat we will note is that we haven’t carefully checked the results from the remainder of the MicrobeAnnotator pipeline. We know that any initally incorrect KOfam annotations will be in the final annotation table, but they may appear alongside better annotations from the other databases, which could ameliorate the effects of the false positives, at least (provided users parse the table to find the best match for a given gene).

Conclusion

This all may seem like bad news. But there is some good news coming out of all this as well. Thanks to the nature of open-source software development, we were able to fix the bugs in MicrobeAnnotator. Here is the PR that we submitted to the MicrobeAnnotator repository on GitHub. The changes have already been merged to the main branch as of February 17, 2024, so anyone installing and using the tool after that point should be good to go.

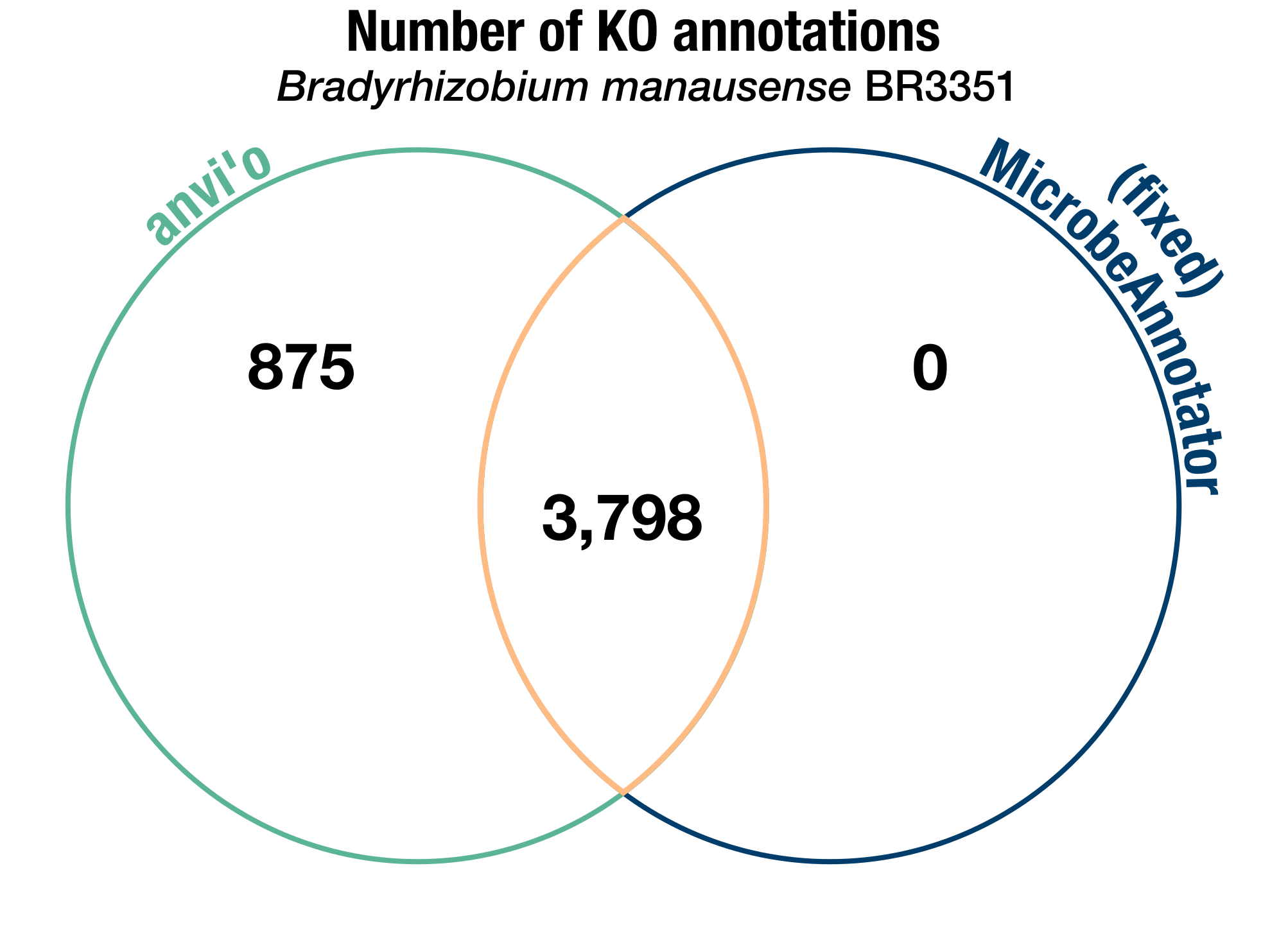

We compared the two software again after fixing the pipeline, and this time, the results were in line with what we expected (with a high number of ‘common’ annotations, some anvi’o-specific annotations, and 0 annotations specific to MicrobeAnnotator when we don’t count the KOs without bit score thresholds):

A Venn diagram of the number of KEGG Ortholog annotations identified in the B. manausense BR3351 genome by either anvi’o, our fork of MicrobeAnnotator in which we fixed the bugs, or both. As in the previous diagram, we don’t include the KOs without bit score thresholds in these counts.

In addition to the good news, we hope that all of us who use and make bioinformatics software can take away a couple of lessons. First, tool development is not infallible, and as developers, we have a responsibility to carefully test our tools. Software development best practices like unit tests, explicit typing, or even simple tricks like comparing the output before and after critical changes, can help reduce insidious bugs like the ones seen here. From the user perspective, using new tools comes with a risk and warrants some extra attention to validate the results that will eventually impact your research.

Most importantly, we hope this investigation and the PR that came out of it serve as a resounding argument for open-source software, especially for scientific applications. If MicrobeAnnotator hadn’t been open-source, we wouldn’t have been able to identify these bugs or have the opportunity to propose corrections. Therefore, we’d like to end by thanking the MicrobeAnnotator developers for supporting open science.